Click for PDF format

Click for English PDF

Click for Arabic PDF

I sang a lot as a child.

I had a throaty voice. My lungs caught bronchitis often and the coughing scratched my throat. Adults found it beautiful.

The older I grew, the less sick I got and the cleaner my voice became.

It wasn’t the same with my mouth.

The older I grew, the filthier it got, as though the phlegm that had chaffed my chords didn’t disappear, but instead, became curses that moved closer to my lips. Closer to the outside world.

This dirtiness sat, behind my teeth, under my tongue, for years.

It festered, and as an adolescent, I had many ulcers. I never let it out. I had pristine school reports, and my teeth were pearly white. But something in my stomach was pushing at my mouth, and the skin broke open and my mouth bled but my words stayed inside.

Then they slowly trickled out. They leaked through my teeth, between my parted lips, first in breaths, then whispers, then words and finally hacking coughs. My chest came full circle.

I think, sometimes, that my body formed around my mouth.

With every cough, a secret tried to escape. The belt of three stars, sea-salt drying on the shore, the taste of waves lapping against stones. My secrets, saffron kisses, like warm winter tea, and words whispered, like thin summer clouds.

But they were inside, pressed together, calcifying, not clouds anymore, but slow rock. Odorless in their immobility, in their imprisonment, tasteless.

Around them, my tongue morphed. My teeth, the teeth I ground to keep the clouds in, bled then broke then, around their debris, regrew anew. My lips flayed, then regenerated, and now they sit, my words’ sore and swollen gates to the world.

I think bodies form around their negative spaces.

Looking for someone else’s secrets, I found fossils in my ears. I took them out and they looked like words, but ones I’d never heard before. They had been sitting there for years. Hardening. Settling. The brackets that held the inside of my head together, and kept my thoughts from tumbling out, kept them from the summer clouds.

I put the words back in, but my ears hadn’t stopped forming, deforming, reforming. The brackets had become loose, the secrets ill-fitting. This is when the headaches started.

I think the words inside my body are the hammer to the anvil of the world outside.

I ignored my headaches. I was sure the problem was the back of my neck. My skin crawled at the smell of saffron, the taste of sea salt. Every morning, I’d wake to summer clouds and my hackles would rise – every night I’d sleep beneath three stars.

It had to be my dreams. They drained out like septic water, clotting my hair, soiling my pillows. They could never fit around my neck, until I redrew my head, re-stretched my spine, replaced my skin.

I slept better then, but I still ached. The sea salt was in my lungs, the sun’s fire in my gullet. I thought of bronchitis like an old friend, and of words like rock and lungfuls of stones, of solidified smoke.

I didn’t smoke, but so many men around me did. I inhaled their tobacco breath and never breathed it out. It stayed inside me and slowly coalesced into a dense cloud of ever-changing unattainabilities.

I think the spaces around my body work in tandem to stop it from being.

Then one day, I decided to start singing again.“Watch your chin, your shoulders,” my instructor would say.

I sang in front of a mirror, and watched the smog leave my body.

How to Make a Person: A Recipe

As published in v.1, Fall 2018, and RISD XYZ Fall/Winter2018/19.

Thirteen centuries ago, an alchemist wrote a recipe for making humans.

Jābir Ibn Hayyan scribed hundreds of books about chemistry and alchemy, astronomy and astrology, engineering, geography, philosophy, physics, and pharmaceuticals and physiology. But it was his thoughts on Creation that attracted me to his work. Jābir talks of three tiers of being—inanimate, simple life, and intelligent life. When I first encountered a reference to his recipe, I wondered: What ingredients turn inanimate matter into a self-determined life, a life with a body granted movement, agency, and personhood?

I wondered about this as I began to dig deeper into my own person, into the liminality of a third-generation refugee body. I was struggling with giving myself permission to talk about politics in my studio work, and finding reprieve where I could speak with my body—with a physicality that exists, skin and flesh and bones, a person—undeniably.

I finally found Jābir’s recipe.

He instructs: “Begin by placing the bones then the flesh and veins and blood vessels and cartilage.”

Could I reverse the recipe, pull the prerequisites of personhood from it and check them against myself? Find proof that my body exists, make its agency indisputable?

But what were my bones? What is my flesh and veins? My bones were kneaded with the Ka’ak1 of every Eid. My flesh baked with the Fatayer2 of every Friday morning, the veins brewed with the ‘Ahwé3 after every Maghrib prayer. I think I congealed in small crucibles of family gatherings.

“Place,” Jābir writes, “each part in its designated location.”

My designated location? I grew up between the sun and the waters of the Arabian Gulf.

I was made Palestinian-Syrian, in a pot two thousand and six hundred kilometers away from Palestine, two thousand and nine hundred kilometers away from Syria. Left to simmer for as long as the road to either place, bound by the sand of Emirati beaches, created an Aristotelian Perfect Mixture that didn’t exist in either place. No hyphens, no capitals, insoluble: palestiniansyrian.

I was fifteen when I first visited Mukhayyam4 AlNeirab to get my ID card. On it was listed my official “place of origin”—AlNeirab Refugee Camp.

I remember entering the camp underneath a wooden arch, the flags of Syria and Palestine on either side of it. I remember the streets were dusty, and the sun was glaring and hot. I remember my dad walking quickly, talking excitedly, the way he does when his day is running on schedule. I don’t remember much else. On that day, I hadn’t wondered what it would’ve been like to grow up there, I hadn’t connected that desolate place to the one my dad’s stories were often set in, to the Damask rose and strawberry farms that bordered it. Would ripe strawberries have dotted the soil with red dust? Would the hot air smell like the soft petals, taste like the rose jam that spills in our suitcases when we fly back to the Emirates?

I was nineteen when I first heard “rejected because of your passport.” A small part-time job I had for months, until the company applied for my labor card and asked me to leave. That, I think, was the first time I was conscious of a need to defend… defend what? I wasn’t sure then.

“Then affix each part of it in its place,” Jābir says.

Once this desire to defend surfaced in my consciousness, I started to see it in everything I did. Over the next few years I found myself pulling close parts of my parent’s culture, like someone collecting the contents of a spilled bag on a crowded street. I did it in a rush to reconcile who I am. I ate more levantine food, I switched from espresso to ‘Ahwe, I spoke more Arabic each day. It was as though I was proving to myself that I am who my papers say I am, justifying the obstacles they represented. I further began to see this urge to defend in every decision my parents had made raising me. Choosing my name, selecting my schools: everything was an ingredient they carefully picked, prepared, and dropped into a cauldron. Everything a defense against eradication, a resistance to self-erasure. To prove we are who we are.

“Make the body out of a glass vessel.”

A body that is hollow, see-through. Not invisible, but almost.

Out of glass, A material of multiple states, often in constant movement, hot and glowing and flowing, but here: still, cold, a container to contain, not to move.

I was twenty-three when I applied for my first travel visa, and when I realized it was my body’s agency I’ve been trying to defend. A body that isn’t, actually, hollow, not see-through. Stateless, yet always of multiple states, always in constant movement. Not hollow, not still, not invisible.

1. Semolina-based, date-stuffed holiday cookies.

2. Open-faced baked breakfast pastries.

3. Coffee, as pronounced in a Levantine dialect.

4. Mukhayyam: Camp

As it appears in E11, a publication by The Center for Architectural Discourse.

Like a stretch of dark, infinite skin, the sky above is smooth and unblemished. You speed underneath that uniform black blue, through a bright blur of streetlights, a ribbon winding up and around, through cities of white and orange flecks; tapestries of attainable, terrestrial constellations.

On this intertwining ribbon, you drive, taking its loops a little too fast, eyes forward and never up, because the universe is far and invisible, and the only galaxies that matter are here, on the ground, with you.

You drive, but sometimes the rush of the wind against the metal of the car is so loud. Sometimes, when the lampposts are passing by too fast to count, when you can’t connect the stars anymore and the constellations have stopped making sense– sometimes you slow down.

Sometimes, you stop.

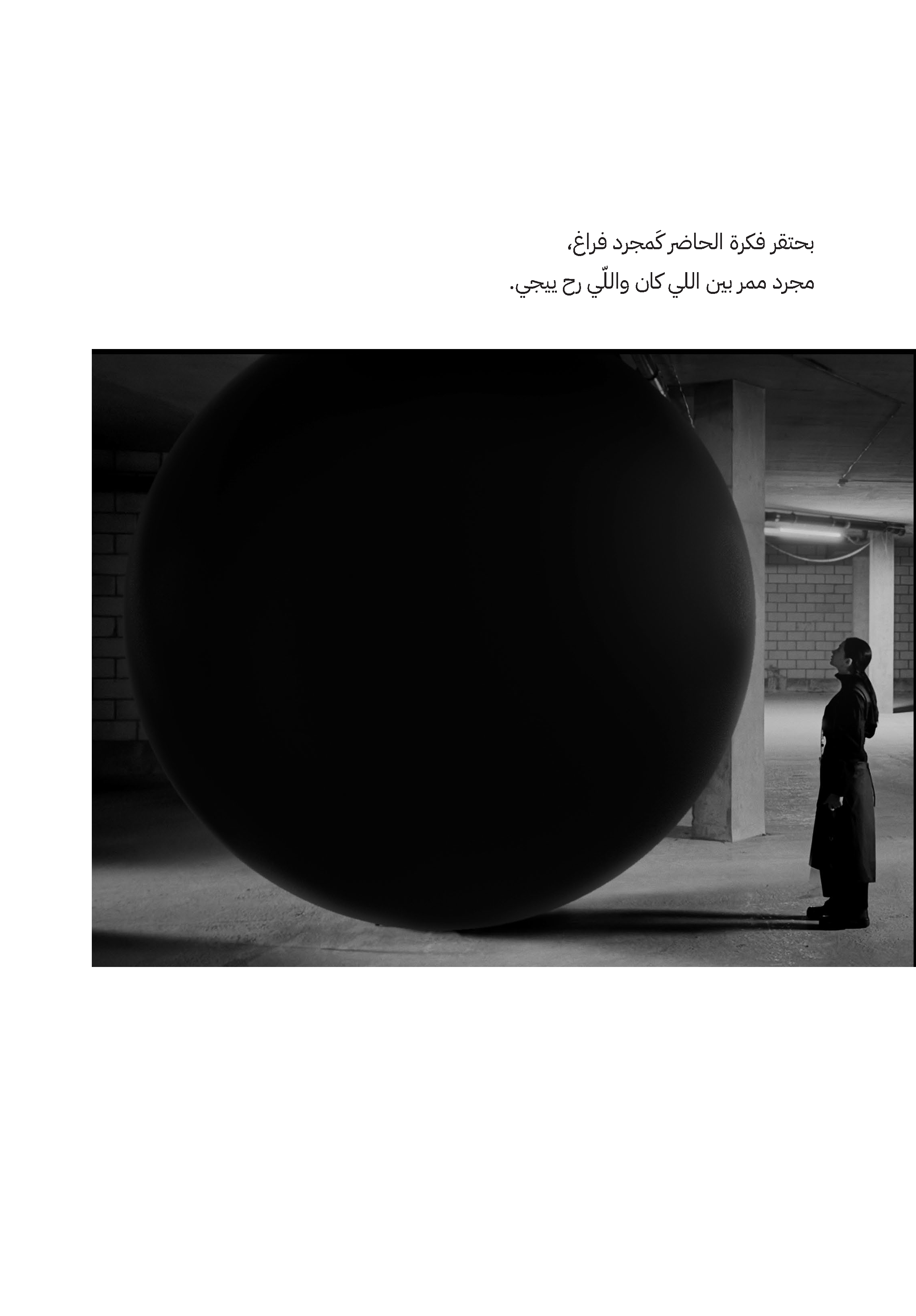

Moments of stillness are rare in this constantly gushing stream of movement, but they exist. Sometimes they are mountainous; big bulking blocks of rocks, demanding a quiet as heavy as they.

Sometimes they are fleeting, those moments. A quiet song on the radio, a soft drizzle on your windshield. A phone-call, a cigarette.

And sometimes–

Sometimes they are transcendent.

They pull you up, and you realise you’ve cramped your neck looking forward for so long. Look up! Look away from your earthy stars, look at the sky; a million suns like summer freckles, a thousand galaxies, pink and blue, like bruised cheekbones.

They take you outside. They take you outside of yourself, outside of themselves. You and they are sharp corners pointing up, cutting edges turning away. You are only waiting, here at those monuments in those monumental moments. Everything is only waiting. Everything is just here until take off.