Renovation and Adaptaion (2014-2017)

SITE

Location

Dasman, 25.353066 N, 55.412170 E

Urban Context

The site is located right on the edge of what used to be the British Camp boundaries. Up until 1972, the British Royal Air Force (and for some part the Trucial Oman Scouts) occupied the camp. It was gated and almost exclusive to British and foreign personnel. The camp was formed in 1932, at the time a good distance from the city of Sharjah. Upon the federation of the United Arab Emirates in late 1971, the camp was technically integrated into the city, and was vacated of all army. By then, the city of Sharjah had expanded to surround the camp boundaries. The gate remained until 1978 and access beyond the boundary was still somewhat restrictive. By then Dasman was becoming an ideal spot for the relocation of families by the government from neighbourhoods susceptible to real-estate development.

Over the years the site became the centre of major road arteries in the city.

Dimension

Plot Area : 2488 sqm / Building Area : 863 sqm

HISTORY

The Flying Saucer is located at the intersection of several residential areas on what used to be known as “The Flying Suacer Roundabout”. This futuristic building was built between 1974 and 1976 (based on aerial views), and was opened to the public at the end of 1978 as a one-stop-shop combining a restaurant, drugstore, pharmacy, newsstand, tobacconist, gift shop, patisserie and delicatessen. It later became a COOP supermarket followed by the fast food chain takeaway chicken restaurant Al Taza. The building was purchased a few years ago while it still served as Al Taza, and was first used in the Sharjah Biennial 12 (SB12) in 2015. To this day it holds many memories for Sharjah residents.

CONCEPTUAL IDEA

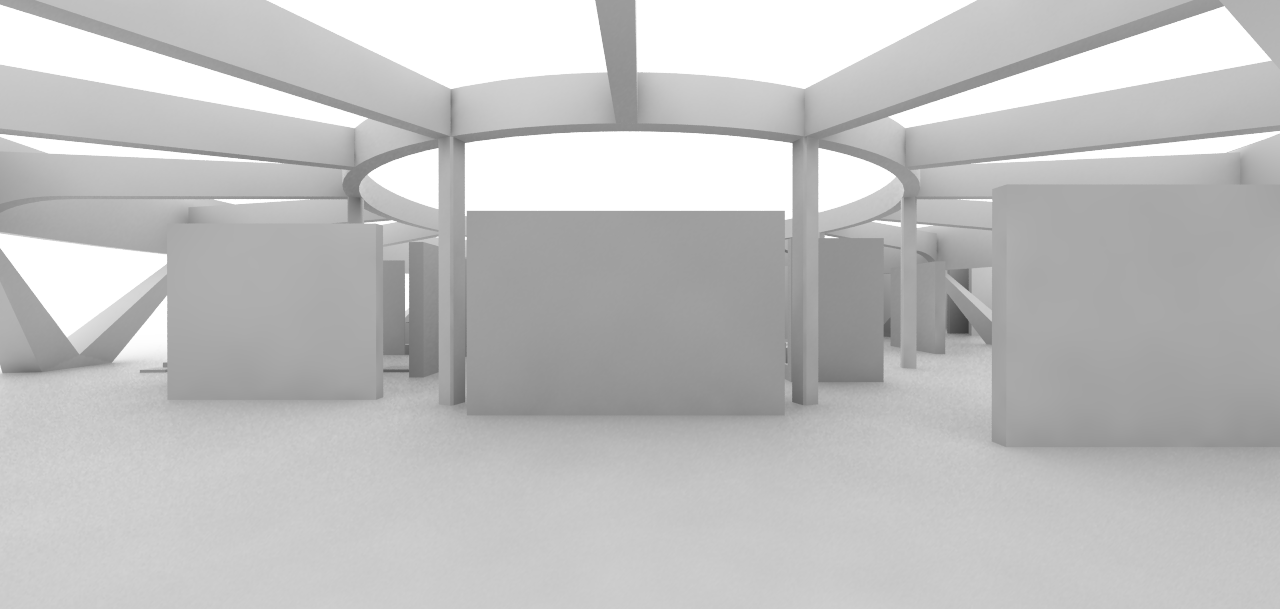

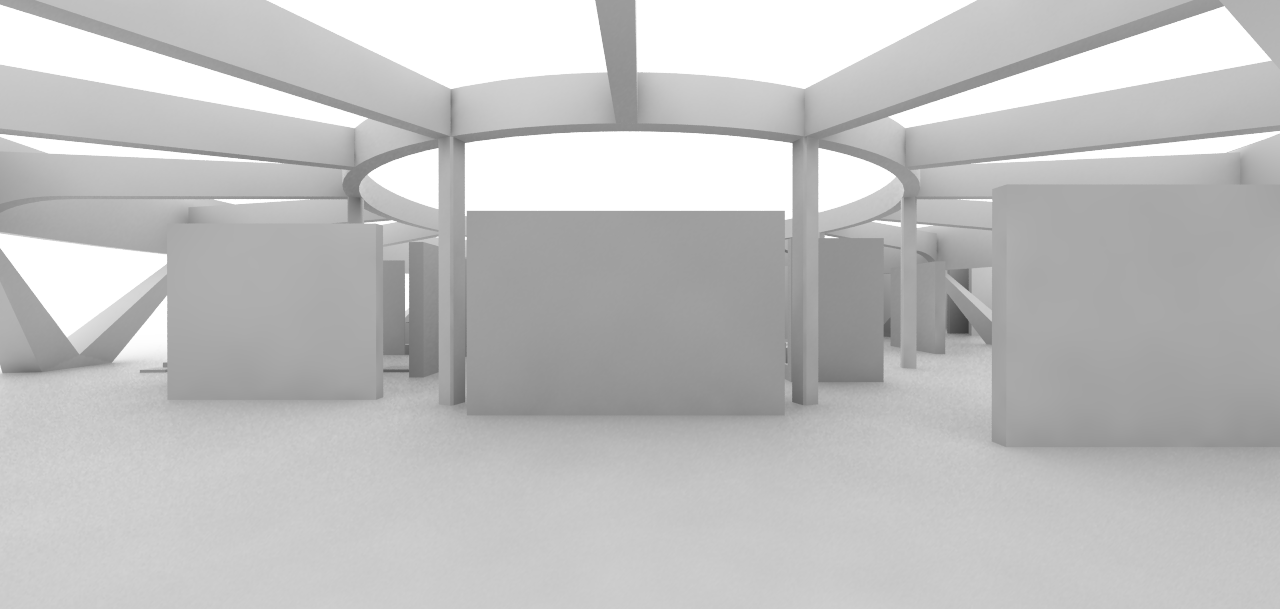

An in-situ Brutalist structure with a panoramic interior, capped by a dome that is flanked by a ring of peripheral spaces, bounded by leaning pillars and enclosed with glass.

STRATEGIES

Urban

One of SAF’s offsite venues, the Flying Saucer sits at the intersection of multiple residential areas (Dasman, Ghubaibah, Yarmouk and Ramla,) on what used to be known as “The Flying Saucer Roundabout.” Close to the center of the city, the Flying Saucer continues to be a landmark for the locals and an icon of the futuristic vision of the seventies.

Spatial characteristics

Believed to be constructed in 1975, the building’s 12.7 m dome is supported by eight columns, around which fans 18 peripheral spaces, defined by the beams running overhead, and encased in the pillars that hold up the light and open interior. Tapered and tilted, these concrete pillars create a complex three-dimensional structural diagram, arrayed in a circle, allowing for a fully glazed facade, and surrounded by a canopy that cantilevers over the building, ending in 32 points.

These elements are all exposed cast-in-place concrete (until it was cladded for the fast food restaurant in the 2000s.) The architect is still unknown, but the space-age influences of the western 60-70s literature & pop-culture, and those of Brutalist architecture of the same period are evident in the design.

In 1978, an annex was added to The Flying Saucer. In 2010, the construction of Al-Wahda overpass is completed, transforming the urban landscape of the area, and placing the Flying saucer in one of the intersection’s corners.

Spatial organization

After the acquisition of the building by the Sharjah Art Foundation, and the initial display of it as a found object in the Sharjah Biennial 12, the Flying saucer underwent renovation, where the cladding and partitions were stripped away to reveal the building’s innate tactile and spatial qualities. The building’s access was initially modified to be only through the annex, providing a threshold, and an interstitial viewing experience of the flying saucer, moving the user from seeing it from the exterior, to a more intimate viewing platform of the building-as-object and its structural elements (as well as the pointed canopy,) before stepping into the space itself.

The annex, in contrast to the very bright and airy space of the flying Saucer, is a dark space, where the viewer, once through the high door, is encountered by two long stretches of wall. A spatial continuity between the annex and the flying saucer is established through materials, as cementitious walls and floors flow between them, and through the revelation of the structural systems that hold up the annex.

To allow for the use of the space as an art gallery all year round, a temporary air-conditioning solution was used through cementitious volumes in the space, aligned to hide the overpass from the interior and conceived as objects within the still open and circular space of the Flying Saucer. Those AC-rooms, housing the interior air handling units that connect to outdoor ones on the roof, have an expressed gap between their top and the Flying Saucer’s peripheral sloping ceiling. They are also hidden behind thick free-standing walls that provide a grill-free surface to display artwork on, and mediate the interaction between the Flying saucer and the solid masses of the AC rooms.

In 2016, a second access was introduced to the flying saucer, allowing the user to immediately exit the building into the outdoor parking and the greater urban context. The new door, not on axis with the existing direction of entry from the annex, emphasizes the 360 degree openness of the flying saucer by subtly rotating the directionality of the space.

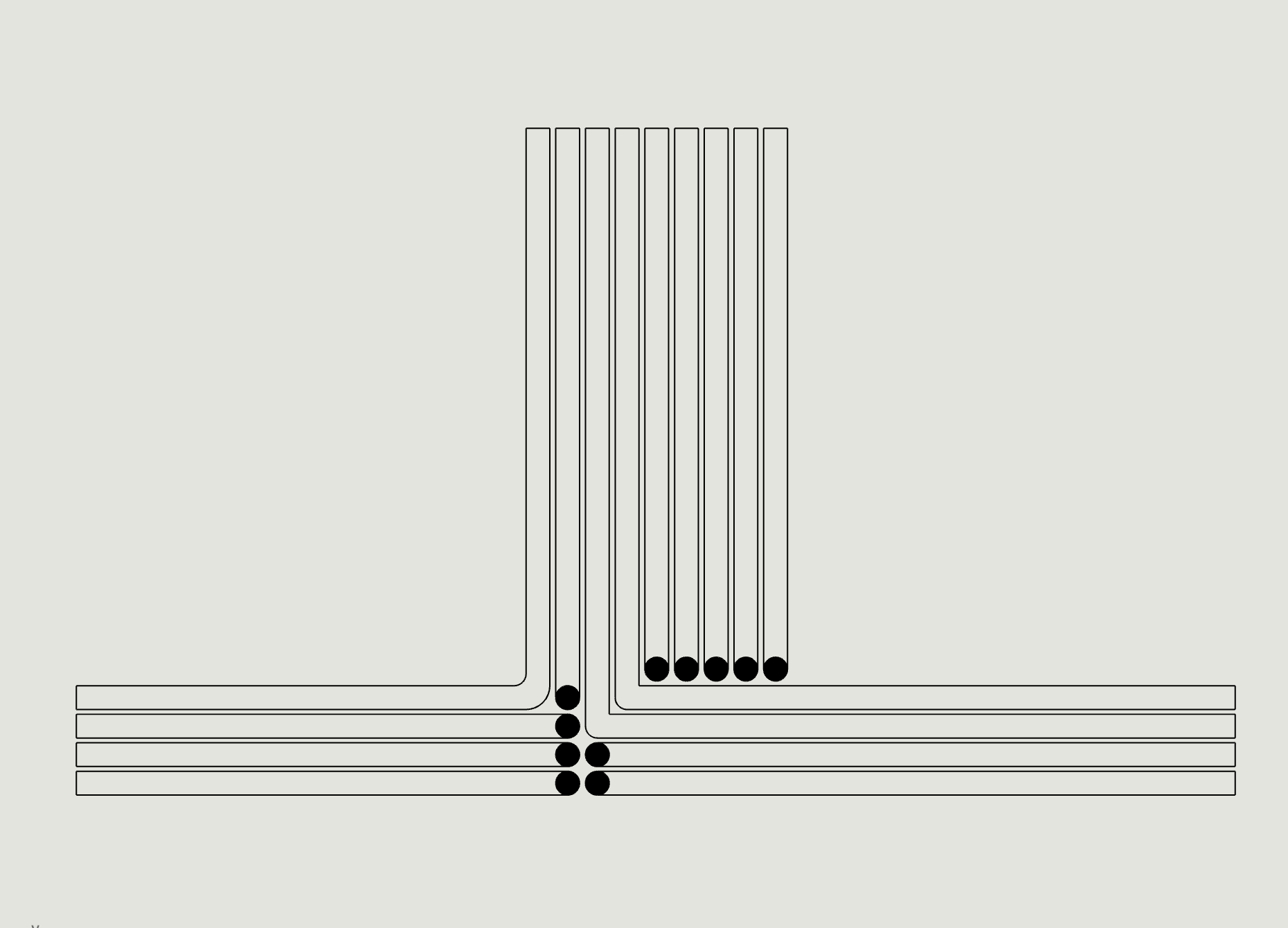

Lighting

As with the structural system, all electrical elements in the Flying Saucer are exposed and expressed. The wiring work climbs the columns and runs around the two structural ring-beams of the flying saucer, making its way to feed the ambient up-lights of the dome, that wash the space with reflected soft illumination, and the smaller up-lights in each peripheral segment. Tracks were installed in parallel to the beams that define each segment, providing flexible opportunities to light artworks in the peripheral spaces. Singlets were also installed at the end of each beam to provide a systematic opportunity to send light into the space under the dome. Tracks were also installed as needed for each exhibition underneath the dome, hanging slightly above the beam ring, to read not as a cap, but as lines within the space of the dome.

Materiality

The Flying Saucer, true to a decisively brutalist ideology, is of expressed cast-in-place concrete. The structural elements are painted white, and the enclosure is completed with tilted glass panels. The interior of the dome is exposed and unplastered, adding a tactile richness to the interior, and displaying signs of age and patina, as well as its construction process, through some exposed rebars.

As above in the dome, so below is the floor of a cementitious material, creating a connection between the horizontal surfaces of the spaces, and allowing the white vertical elements to descend slightly in hierarchy, enhancing the openness of the space to its surrounding.

Proposed permanent adaptation

Spatial re-organization

The horizontally extended and vertically compressed underground space contrasts with The Flying Saucer’s open and airy character. A round underground courtyard with lush vegetation brings light down into the underground space and dialogues with the dome of The Flying Saucer.

In addition to the exterior staircase linking the basement level to The Flying Saucer, an internal staircase takes the user directly from the underground space into the interior of The Flying Saucer.

The basement provides space for the programmatic requirements, such as a cafe, a private rehearsal space, and a meeting/work/study area with the ability to use it for functions and workshops/lectures. It will also contain all the MEP equipment, allowing for the HVAC system

to run underneath the Flying Saucer, with grills on the floor placed around the periphery, allowing the characteristic ceiling structure to remain exposed and free of clutter.